❔EMH FAQ (Frequently Asked Questions)

🙋 What is passive management?

See answer

✔ Passive management means that you aren’t actively stock picking. Typically this means that the investor purchases a mutual fund that in turn uses their money to purchasea mutual fund that buys all securities in a given market index. For example, an S&P 500 index fund is a passive fund that simply purchases the 500 stocks in the S&P 500 index. It purchases each stock in proportion to its weight in the S&P 500 index.

🙋 In Connect, can I see my results before the due date?

See answer

✔ Unfortunately, Connect doesn’t let you do that until the due date. You do get to see your score, though.

Brain Food FAQs

These questions go beyond what you need to know for this class.

🙋 If markets are efficient, how do arbitrageurs make money? Is there something self-defeating about EMH? (“Grossman Stiglitz”)

See answer

Full question:

🙋 Isn’t there something circular about the EMH? It requires sophisticated traders to work hard to identify mispriced securities, but it says that those traders won’t make any profits! Clearly, if markets are highly inefficient, arbitrageurs will attempt to profit off of this inefficiency and will therefore make the markets more efficient. However, if markets are already fairly efficient, arbitrage won’t be as profitable. What incentives will arbitrageurs have to seek out the remaining slightly mispriced securities? The profit they make won’t justify the costs of their efforts. Therefore, a correct understanding of the action of arbitrageurs implies that markets will always be slightly inefficient.

✔ Great point. This argument was made by Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz and his coauthor Sanford Grossman in a 1980 paper. It is as if the arbitrageurs eat up their own profits by making the markets more competitive.

Their paper presents a mathematical argument, essentially based on game theory. The scholars reading it could verify the correctness of the proofs it contained, so that afterwards it was impossible to treat their argument as mere hand-waving. They were able to derive a new equilibrium in which the marginal arbitrageur is just compensated for the work of seeking out mispriced securities.

My takeaway:

The work of arbitrageurs can reduce security mispricings, but only to the point where there is still enough mispricing to motivate the arbitrageurs.

In their own words… From Grossman and Stiglitz, 1980, page 404:

The only way informed traders can earn a return on their activity of information gathering, is if they can use their information to take positions in the market which are “better” than the positions of uninformed traders. “Efficient Markets” theorists have claimed that “at any time prices fully reflect all available information” (see Eugene Fama, p. 383). If this were so then informed traders could not earn a return on their information.

We showed that when the efficient markets hypothesis is true and information is costly, competitive markets break down. This is because when or , , and thus price, does reflect all the information [Rob: ignore this sentence - I only leave it in to show how their mathematical model, which takes up most of their article, intersects with their intuitive argument]. When this happens, each informed trader, because he is in a competitive market, feels that he could stop paying for information and do as well as a trader who pays nothing for information. But all in- formed traders feel this way. Hence having any positive fraction informed is not an equilibrium. …

We are attempting to redefine the Efficient Markets notion, not destroy it. We have shown that when information is very inexpensive, or when informed traders get very precise information, then equilibrium exists and the market price will reveal most of the informed traders’ information

The best arbitrageurs are like an ouroboros, making it impossible for the weaker arbitrageurs to make a living doing arbitrage:

🙋 🧠 Benjamin Graham on EMH

See answer

Full Question:

🙋 On page 645, Chapter 19 in the Bodie, Kane and Marcus they quote Graham as saying:

“technique confines itself to the purchase of common stocks at less than their working capital value, or net current-asset value giving no weight to the plant and other fixed assets and deducting all liabilities in full from the current assets”

Would you be able to do a calculation to help me understand how they compare this to the stock price please? In slides 6 Oct 18 the balance sheet and income statement for Home depot appears on slides 65 and 83 respectively. Would you be able to use these numbers to show how Graham computes his values for me please?

PS - Whether right or wrong in whatever form I find the discussions/arguments on EMH fascinating.

✔ Let’s take a look. Here is the quote in question, from our textbook.

-

19.7 Value Investing: The Graham Technique

No presentation of fundamental security analysis would be complete without a discussion of the ideas of Benjamin Graham, the greatest of the investment “gurus.” Until the evolution of modern portfolio theory in the latter half of the 20th century, Graham was the single most important thinker, writer, and teacher in the field of investment analysis. His influence on investment professionals, among them his now equally famous student Warren Buffet, remains very strong. -

Graham’s magnum opus is Security Analysis, written with Columbia Professor David Dodd in 1934. Its message is similar to the ideas presented in this chapter. Graham believed careful analysis of a firm’s financial statements could turn up bargain stocks. Over the years, he developed many different rules for determining the most important financial ratios and the critical values for judging a stock to be undervalued. Through many editions, his book has been so influential and successful that widespread adoption of Graham’s techniques has led to the elimination of the very’ bargains they are designed to identify. [Rob: this is an example of how arbitrage activities destroy the opportunities for arbitrage. Don’t take it as discouraging, though, as the book had been out for 42 years before the activities of arbitrageurs eliminated the mispricings the book helped identify. In the intervening years there was plenty of opportunity for profit, and it’s still a great book.]

-

In a 1976 seminar, Graham said:

-

I am no longer an advocate of elaborate techniques of security analysis in order to find superior value opportunities. This was a rewarding activity, say, forty years ago, when our textbook ‘“Graham and Dodd” was first published; but the situation has changed a good deal since then. In the old days any well-trained security analyst could do a good professional job of selecting undervalued issues through detailed studies; but in the light of the enormous amount of research now being carried on, I doubt whether in most cases such extensive efforts will generate sufficiently superior selections to justify their cost. To that very limited extent I’m on the side of the “efficient market” school of thought now generally accepted by the professors***.*** (As cited by John Train in Money Masters (New York: Harper & Row, 1987)

-

-

Nonetheless, in that same seminar, Graham suggested a simplified approach to identifying bargain stocks:

-

My first, more limited, technique confines itself to the purchase of common stocks at less than their working-capital value, or net current-asset value, giving no weight to the plant and other fixed assets, and deducting all liabilities in full from the current assets. We used this approach extensively in managing investment funds, and over a 30-odd-year period we must have earned an average of some 20 percent per year from this source. I consider it a foolproof method of systematic investment-once again, not on the basis of individual results but in terms of the expectable group income.

-

I think that Graham and Dodd is a great book, but I find it more valuable for the psychology that it inspires than for the specific techniques that it provides. Warren Buffet if famous and beloved for a certain risk averse and folksy approach he brings. Perhaps not coincidentally, Graham and Dodd help convey this common-sense risk-averse approach. I think it is valuable.

With that said, many of the specific techniques advocated by G&D feel somewhat out of date. Graham and Dodd’s emphasis on comparing the book value of a company to the market value is an example of this. The book value is the value of the company as derived from its accounting “books” and is roughly comparable to shareholder’s equity. They argue that if the accounting value of the company is greater than the market cap of the company, it is a great value and you should buy it.

Of course you should! With so many valuable assets, management should be able to turn the company into a very profitable source of cash flows. If they can’t, you could liquidate the company and its value would be approximately equal to its book value (if the accounting data is solid, and G&D would never suggest investing in a company where you have doubts about the bookkeeping). Because the book value is greater than the market cap, you would still make a profit.

But when are you going to find something like that today? You won’t. Professional investors will have already driven up the price of a firm like this. An activist investor may already be circling around the firm to liquidate it and sell portions off, driving the market cap up until it is equal to the book value.

Unless it takes advantage of a specific inefficiency in the system, no mechanical method of stock picking will work for long. For mere mortals (ie people who aren’t Warren Buffet), competition drives the returns down, as the EMH teaches us. As I often say, if investment management were easy, it wouldn’t be so very lucrative.

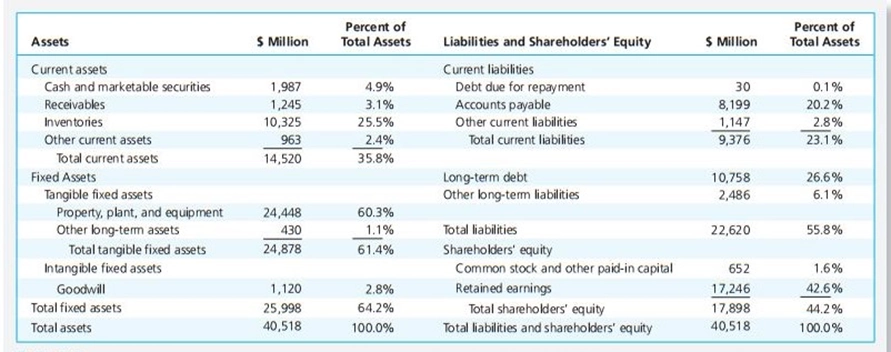

Consolidated Balance Sheet for Home Depot, 2012:

“technique confines itself to the purchase of common stocks at less than their working capital value, or net current-asset value giving no weight to the plant and other fixed assets and deducting all liabilities in full from the current assets”

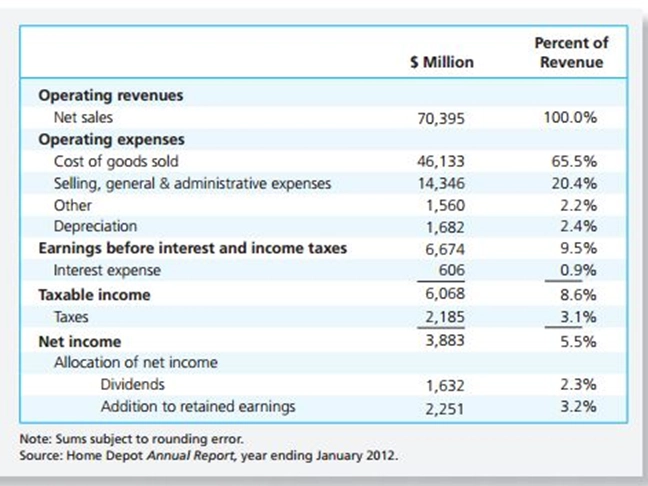

Working Capital = Current Assets - Current Liabilities = 14520 - 9376 = 5144 =$5.144 Billion.

Graham’s advice in this case boils down to saying that if the market cap drops below $5.144 billion, then it is a clear buy.

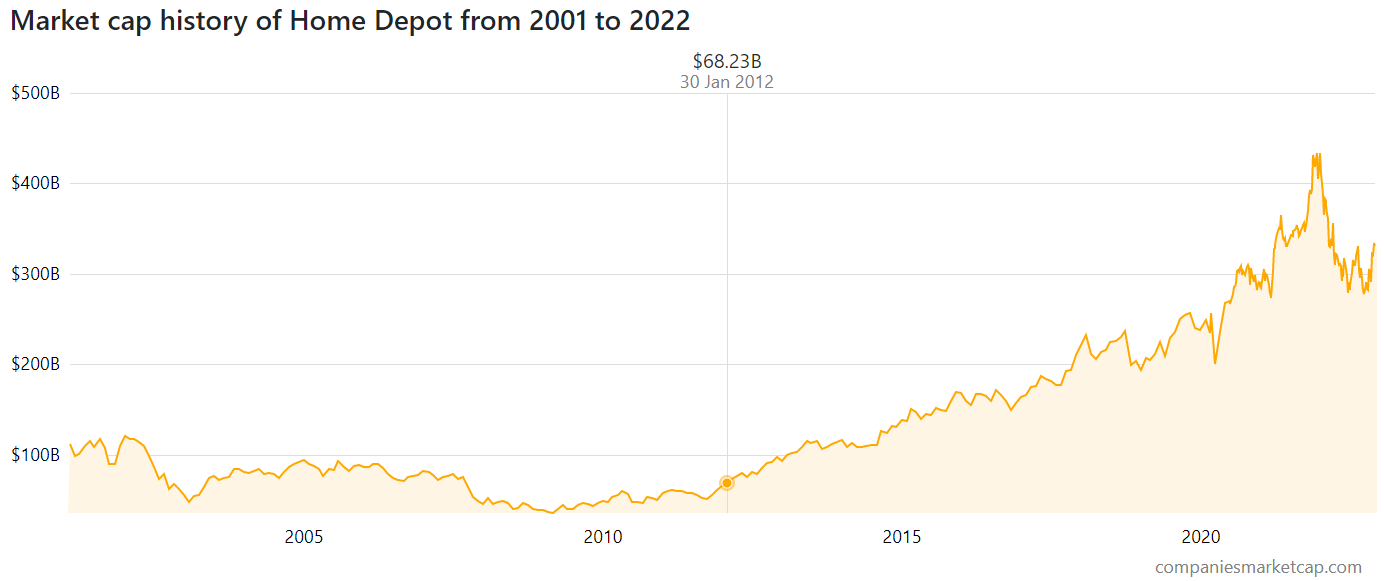

Home Depot’s actual market cap in January of 2012 was $68.23 B, and it rose significantly after then:

I’ve managed to make Graham look pretty bad here, right? But Warren Buffett looks up to him as a hero, and Warren Buffett has made more money in the stock market than I have.

I think that Warren Buffett looks up to Graham because he was Graham’s student and Graham taught him how to think more prudently and clearly about investing. Often in university education, it is not the individual ideas that matter - rather it is the methods of thinking that you learn. I try to emphasize this throughout our sections. For example, I simultaneously bash the CAPM and praise it, saying that what is most valuable about it is the way that it gives you a model for thinking about securities markets. I think that education is often about methods of thinking rather than specific results. Clearly, Graham’s idea of purchasing cheap stocks is very clearly thought out and will help you preserve your capital. It may not have aged well, but the ability to think clearly and identify opportunities is timeless.

(By the way, did Home Depot really get 6 times more valuable between 2012 and 2021? This might make you wonder whether the market cap truly represents the inherent value of the company.)

Here is what Buffett has written about the book:

FOREWORD BY WARREN E. BUFFETT

There are four books in my overflowing library that I particularly treasure, each of them written more than 50 years ago. All, though, would still be of enormous value to me if I were to read them today for the first time; their wisdom endures though their pages fade.

Two of those books are first editions of The Wealth of Nations (1776), by Adam Smith, and The Intelligent Investor (1949), by Benjamin Graham. A third is an original copy of the book you hold in your hands, Graham and Dodd’s Security Analysis. I studied from Security Analysis while I was at Columbia University in 1950 and 1951, when I had the extraordinary good luck to have Ben Graham and Dave Dodd as teachers. Together, the book and the men changed my life.

On the utilitarian side, what I learned then became the bedrock upon which all of my investment and business decisions have been built. Prior to meeting Ben and Dave, I had long been fascinated by the stock market. Before I bought my first stock at age 11-it took me until then to accumulate the $115 required for the purchase-I had read every book in the Omaha Public Library having to do with the stock market. I found many of them fascinating and all interesting. But none were really useful.

My intellectual odyssey ended, however, when I met Ben and Dave, first through their writings and then in person. They laid out a roadmap for investing that I have now been following for 57 years. There’s been no reason to look for another.

Beyond the ideas Ben and Dave gave me, they showered me with friendship, encouragement, and trust. They cared not a whit for reciprocation-toward a young student, they simply wanted to extend a one-way street of helpfulness. In the end, that’s probably what I admire most about the two men. It was ordained at birth that they would be brilliant; they elected to be generous and kind.

Misanthropes would have been puzzled by their behavior. Ben and Dave instructed literally thousands of potential competitors, young fellows like me who would buy bargain stocks or engage in arbitrage transactions, directly competing with the Graham-Newman Corporation, which was Ben’s investment company. Moreover, Ben and Dave would use current investing examples in the classroom and in their writings, in effect doing our work for us. The way they behaved made as deep an impression on me-and many of my classmates-as did their ideas. We were being taught not only how to invest wisely; we were also being taught how to live wisely.

The copy of Security Analysis that I keep in my library and that I used at Columbia is the 1940 edition. I’ve read it, I’m sure, at least four times, and obviously it is special.

But let’s get to the fourth book I mentioned, which is even more precious. In 2000, Barbara Dodd Anderson, Dave’s only child, gave me her father’s copy of the 1934 edition of Security Analysis, inscribed with hundreds of marginal notes. These were inked in by Dave as he prepared for publication of the 1940 revised edition. No gift has meant more to me.

Graham, Benjamin; Graham, Benjamin; Dodd, David; Dodd, David. Security Analysis: Sixth Edition, Foreword by Warren Buffett (Security Analysis Prior Editions) (pp. 17-18). McGraw-Hill Education. Kindle Edition.

Consolidated Statement of Income for Home Depot, 2012: