🔎 Taxes for discount bonds

How the textbook explains it:

After-Tax Returns

The tax authorities recognize that the “built-in” price appreciation on original-issue-discount (OID) bonds such as zero-coupon bonds represents an implicit interest payment to the holder of the security. The IRS, therefore, calculates a price appreciation schedule to impute taxable interest income for the built-in appreciation during a tax year, even if the asset is not sold or does not mature. Any additional gains or losses that arise from changes in market interest rates are treated as capital gains or losses if the OID bond is sold during the tax year.

| Example 14.12 Taxation of Original-Issue-Discount Bonds Continuing with the example in the text, if the interest rate originally is 10%, the 30-year zero will be issued at a price of . The following year, the IRS will calculate what the bond price would be if the yield were still 10%. This is 63.04. Therefore, the IRS imputes interest income of . This amount is subject to tax. Notice that the imputed interest income is based on a “constant yield method” that ignores any changes in market interest rates. If interest rates actually fall, let’s say to 9.9%, next year’s bond price will be . If the bond is sold, the difference between $64.72 and $63.04 will be treated as capital gains income and taxed at the capital gains tax rate. If the bond is not sold, then the price difference is an unrealized capital gain and will not result in taxes in that year. In either case, the investor must pay taxes on the $5.73 of imputed interest at whatever tax rate applies to interest income. |

The procedure illustrated in Example 14.12 applies as well to the taxation of other original-issue-discount bonds, even if they are not zero-coupon bonds. Consider a 30-year-maturity bond issued with a coupon rate of 4% and a yield to maturity of 8%. For simplicity, we will assume that the bond pays coupons once annually. Because of the low coupon rate, the bond will be issued at a price far below par value, specifically at $549.69. If the bond’s yield to maturity is still 8%, then its price in one year will rise to $553.66. (Confirm this for yourself.) The pretax holding-period return (HPR) is exactly 8%:

The increase in the bond price based on a constant yield, however, is treated as interest income, so the investor is required to pay taxes on the explicit coupon income, $40, as well as the imputed interest income of $553.66 - $549.69 = $3.97. If the bond’s yield actually changes during the year, the difference between the bond’s price and the constant-yield value of $553.66 will be treated as capital gains income if the bond is sold.

Concept Check 14.7

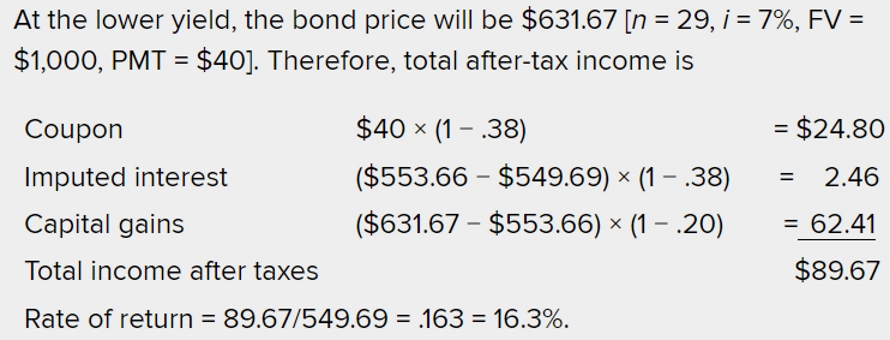

Suppose that the yield to maturity of the 4% coupon, 30-year-maturity bond falls to 7% by the end of the first year and that the investor sells the bond after the first year. If the investor’s federal plus state tax rate on interest income is 38% and the combined tax rate on capital gains is 20%, what is the investor’s after-tax rate of return?

Solution

A simple rule of thumb

Once you’ve read and understood the material above and see how it is applied in the following example, a pair of simple rules may help you remember the results:

For regular bonds:

- coupon payment is interest and is taxed at higher rate

- price appreciation is capital gains and is taxed at lower rate.

- when prices fall, that is a capital loss and it lessens your tax bill (at the lower rate)

For bonds with an Original Issue Discount: (including zero coupon)

- “constant yield price appreciation” is interest

- remaining price appreciation is capital gains.

A basic example

To complement the textbook, a simple example may help: suppose you purchase a zero coupon bond at a yield of 10% and sell it a year later. As Bruce explained during lecture, if the yield stays constant, the bond price will rise as time passes. Suppose the yield stays constant at 10% over the course of the year and the bond’s price rises from $385.54 to $424.10. This $38.56 of price appreciation is viewed as an interest payment for owning the zero coupon bond.

Suppose the company reports excellent news and, as a result, the yield on the bonds fall from 10% to 8%. In this case, the bond price will rise even further, to $500.25. The total price appreciation will be $114.71, butthe IRS will only view the first $38.56 of price appreciation as a form of interest. This is because, as we saw above, $38.56 would have been the level of price appreciation if there hadn’t been the good news and the yield had stayed at 10%. If your tax bracket is 35%, then you will pay $38.56×35% on this.

You willalsobe taxed on the remaining $76.15 of price appreciation. However, this will be considered capital gains, so you will be taxed at that rate. Therefore, if your capital gains tax rate is 20%, then your total tax bill will be $38.56×35% + $76.15×20%.

For bonds that weren’t issued at a discount, the process is much simpler. You apply the general tax rate to any coupon payments and you apply the capital gains income rate to any price appreciationor price loss. This means that any capital loss shoulddecreaseyour tax bill. If you answered the question by ignoring a capital loss and have already submitted your assignment, please let me know!

I’ve done a full writeup of this example in an Excel spreadsheet, showing each of the calculations. It can be foundhere.

An example with more complex taxation

✏ Suppose you have three bonds. Each has a maturity of 5 years and pays annual coupons. Suppose each have a YTM of 10% when you purchase them. They have coupon rates of 12%, 10%, and 0%.

a.) Suppose you sell the bonds one year later. Given the sales price the bonds have a YTM of 10%. What are your pre-tax returns and taxes for the three bonds?

b.) Suppose instead that when you sell them, the bonds have a YTM of 8%. What are your pre-tax returns and taxes for the three bonds?

🙋 Suppose my coupon rate = 10%, YTM = 8%, T = 7, and face value = 1000, the PV would be $1,104.12 according to the formula. At the end of the year, PV would be $1092.46 (T=6). Would the imputed interest income = $1092.46 - $1,104.12 = -$11.67? I wonder if this is how I should calculate the imputed interest income for this particular value. In that case, the imputed interest after-tax income would also be negative. Then, the total income after taxes would include the negative value. Somehow, the investor made less money.

✔ You only have to calculate imputed interest when the bond is issued at a discount. Because this bond was issued at a premium price, there is no “Original Issue Discount” taxes due. Rather, if you sold the bond, the decrease in the price would be a capital loss.

For any bond that is issued at Face Value or above, Coupon income is taxed at the tax rate for regular income and any price changes are taxed at the capital gains rate. In particular, if the value of the bond drops, then the capital loss can be used to decrease your overall tax bill.

In this example, you would pay the regular income tax rate on the $100 of coupon interest, but you would essentially have negative taxes on -$11.67 of loss of value of the bond. If your regular income tax rate is 35% and your capital gains rate is 10%, then your total tax bill will be: